Updated for 2021

It’s that time of year! If you are applying to graduate school and are overwhelmed at the prospect, don’t worry, that’s completely normal! Today’s article is the first of a two part series about applying and selecting a graduate program, specifically in PER. Let’s focus on the picking programs and applying part now and in the spring, we’ll cover how to select which program to attend.

First, some disclaimers. This guide is one of many perspectives of applying to graduate school. While I study graduate admissions in physics, I am a white male who graduated from a research-intensive university as an undergraduate and hence, my perspectives are informed by those privileges.

Before applying

Before you can apply to graduate programs, you first have to determine which programs interest you. A helpful starting point is to consider why you want to go to graduate school and what you are hoping to get out of it. You want to make sure that the programs you apply to support your goals.

Once you have your why and what, you can start to think about the where. One resource for identifying grad programs is AIP’s GradSchoolShopper.

There are also student-created lists of programs such as University of Pittsburgh graduate student and PERCoGS (PER Consortium of Graduate Students) publicist Danny Doucette’s US PhD program list and Western Michigan University graduate student and PERCoGS president Diana Sachmpazidi’s list of science education programs.

Comparing programs

Most graduate programs will follow a common structure. During your first and second year you take classes, then you complete some type of comprehensive exam, and after that you work on your dissertation and the associated research. However, the details vary between programs and PER is no exception.

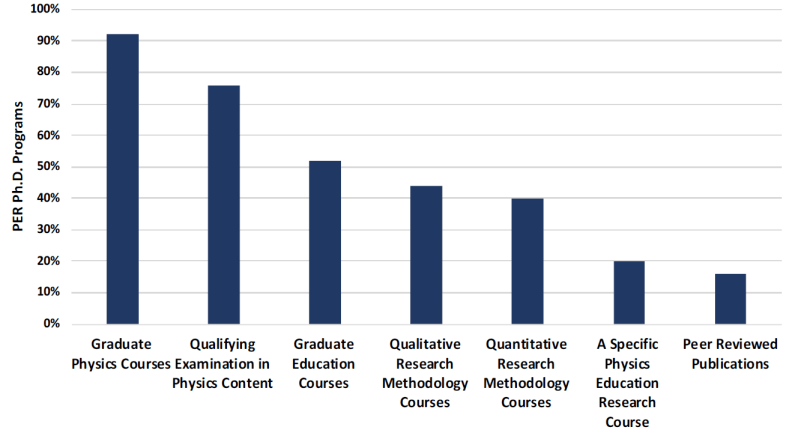

A recent paper surveyed PER Ph.D. programs in the US and found that most are in physics departments but some are not. As a result, most PER graduate students will take traditional graduate physics courses and complete physics comprehensive or qualifying exams. However, there is much variation when it comes to the education part of physics education. Some programs require graduate education courses, some require quantitative or qualitative methodology courses, and some require a PER specific course. For specifics, you’ll have to check with each graduate program.

It’s easy to only focus on the program itself but don’t forget about the physical location of the program. Eventually the pandemic will end and full in-person will resume so you will have to live near your school for a few years. Make sure you can tolerate the climate and enjoy your favorite recreational activities in the area where your potential graduate schools are.

Identifying advisors

So far, we’ve talked about programs, but even more important is the thesis advisor you pick. Your thesis advisor is the one who supervises your research, guides your degree progress, and should serve as a mentor. Having a bad or toxic thesis advisor will make your graduate school experience miserable and will likely impact your career too.

For each program you are interested in, make sure to check out their research areas and the research interests of the faculty. Departmental webpages or personal website may list these as well as recent publications and presentations (Google Scholar can also be a good resource). These can give you an idea of what the group has been up to.

This next bit of advice is controversial in that not everyone agrees that it is necessary or that you should do it. However, reaching out to potential thesis advisors can be a good way to see what research they are actually doing (webpages aren’t always up to date and not all research being done has been published yet) and if they are taking students. PhDs in PER are typically funded (i.e. you are paid a stipend to cover basic living expenses) so thesis advisors need to have grant money to take you as a student. Even if you are a stellar applicant, if your potential advisor can’t cover your funding package according the university’s rules, they may not be able to have you join their lab.

Further reaching out to potential advisors may be useful for admissions. Physics graduate admissions are often decentralized which means faculty from the department decide who gets admitted. For some departments, this means a central committee reads through all applications while for others, faculty in the specific research area read through the applications in their area. Already having contacted faculty members and showing interest in them may offer you an advantage.

A few words of caution however. First, don’t send an email to everyone in department. A generic email to every professor isn’t going to be received well. Show that you’ve put effort in on your end and personalize it with respect to what the professor is doing. Second, don’t be discouraged if you don’t get a response or even get a nasty response. These may be red flags and you may want to rethink working with that person.

Also, when looking for potential advisors or programs, don’t forget to ask your current professors! They may be able to recommend programs or advisors, especially if they are conducting research in the field you are planning to apply to.

Learning more about your thesis advisor

Typically once you are accepted to a program, the program will hold a visit day where you can chat with potential advisors and current graduate students. However, there is nothing wrong with reaching out to current graduate students to learn about their experience in the program before you apply. Many current PER graduates are part of the PERCoGS Slack channel, which you can join by sending an email to [email protected] .

Applying to Programs

Now that you’ve identified programs of interest, it’s time to start applying! Before you start to apply, make a list (yes, an actual written or typed list) of what each program requires, when the deadline to apply is, and any associated fees (application fee, transcript fees, etc.). With coronavirus closing many test centers, pay special attention to each program’s policies around the GRE, physics GRE, and (if you are a non-native English speaker), TOEFL. Also, if you are not able to afford the application fees, many programs do have a fee waiver program through the department, the graduate school, or other organization. For example, if you are applying to any program in the Big Ten, there is a conference wide fee waiver program.

Parts of the Application Package

Many programs will require you to fill out an application, submit a few statements, and submit multiple letters of recommendation. Some will also require you to submit GRE scores. While there is some variation in what types of statements you will be asked to submit, they generally fall into three groups: a personal statement, a research statement, and a diversity statement. For a general overview of what physics admissions committees are looking for, see Owens et al 2019. The main takeaways from the paper are included as part of the following sections.

GRE Scores

Programs are increasingly dropping GRE requirements or making them optional. However, some programs still require applicants to submit general GRE and physics GRE scores. For physics and astronomy programs, you can check the current policies in this spreadsheet compiled by James Guillochon.

Personal Statement

The personal statement is an opportunity for you to introduce yourself to the admissions committee and explain why you want to attend their program. In your statement, you will want to explain your personal journey and what your motivation for attending graduate school is. In this statement, you can and should include work experience, extracurricular activities, leadership roles, and any other experience relevant to why you would make an excellent student in their program. If you have any low grades (think below a “B” or 3.0), you should address why that is, especially if there were extenuating circumstances.

Admissions committees are also beginning to focus on non-cognitive skills such as self-motivation, resilience, and self-learning. If you can show examples of how you’ve used these skills before, do so!

Research Statement

The focus on a research statement is exactly that, research. This includes both previous research experience and what you hope to do in the future. You can and should also think about showcasing non-cognitive skills here too.

When talking about previous research experience, focus on the skills you developed, especially if they are relevant to what you hope to do in graduate school. Have you conducted and coded interviews before? Say so! Did you have to teach yourself these skills? Say so!

Don’t worry if you don’t have all the skills needed to do the research you want to do. Graduate school is supposed to be about developing your skills so you shouldn’t be expected to come in as a polished researcher.

The same is true for publications and conference presentations. If you have these, great. If not, no problem. If a program is expecting these, it might be a red flag that their program is more interested in what their students produce rather than what they learn.

For the future part, you will want to focus on how the program aligns with your interests. What research are they doing that you want to be a part of? This is also a great place to identify which faculty members you are interested in having as your thesis advisor.

When talking about what you plan to research, remember it is just a plan. You aren’t committing to actually study that and your research probably won’t be exactly what you planned (mine isn’t even remotely close). The point of the future research plan is to give the admission committee an idea of how you would fit in their program and whether your interests align with what they do.

Diversity Statement

Diversity statements are becoming increasingly common in academic applications so some of the programs to which you apply may require them. In short, the purpose of the diversity statement is to explain how you will contribute to the diversity of the program.

First, note that “contribute” doesn’t mean you have to identify as part of some minoritized group. For example, some states have laws that explicitly ban affirmative action for college admissions, meaning that graduate programs cannot take gender or race into account when choosing who to admit. You can talk about diversity from the perspective of either a targeted or non-targeted group when it comes to privilege or how you will contribute.

Second, diversity extends beyond gender and race. Your socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, first generation status, disability status, and veteran status can all be contributions to the diversity of the institution. Make sure to be using the appropriate terms as well. The American Psychological Associations’ Bias Free Language guide, the National Center on Disability and Journalism’s Disability Language Style Guide, and the Trans Journalists Association’s Style Guide can help with your language.

For writing your diversity statement, University of Missouri professor Samniqueka Halsey compiled a great list of dos and don’ts. The key points: talk about your values related to diversity, experiences working with diverse populations, and future plans related to inclusivity. Include examples of what you’ve done including courses taken, seminars attended, and literature you’ve read, and finally, explain how you have been an ally and how you will continue to be one.

Remember, if a program asks for a statement of diversity, it means they care about diversity. Don’t put any less effort into this statement than you would the personal statement or research statement. A paragraph or two won’t cut it.

Letters of Recommendation

Nearly all programs will require you to obtain letters of recommendation, though the specific number varies (3 seems to be typical). Make to sure to keep track of how many each program needs and how your letter writers need to submit them (might be an online portal, an email to the head of the admissions committee, or gasp, snail mail).

Many of your peers are also applying to graduate school so make sure to ask early (like now).

When selecting your letter writers, you want your letter writers to be able to discuss different aspects of you. For example, your reference letter writers might be the professor who supervised your research, a professor who taught you in class, and the advisor for one of the student organizations you were part of.

Depending on your letter writer, they may want to include you in the writing process. Some may request your personal statement, research statement, and C.V. while others may have you fill out a questionnaire about what you want them to discuss. Some might even ask you to write a first draft. In any case, make sure to clarify what, if anything, your letter writer needs to write your letter. The letters are to help you so make sure you help your letter writer create the best letter for you.

In case you are wondering, it’s okay (and encouraged) to send reminder emails to your letter writers. Faculty are busy and it’s easy to lose track of deadlines.

It’s also appropriate to ask your letter writers if they will be able to write a strong letter for you. By a “strong letter,” I mean one that includes specific examples and speaks to your character. A generic letter or a negative letter will not help you in the admissions process. Some potential letter writers may not know you well enough to write a strong letter and it’s better to know that before they submit the letter. Make sure to thank them for their honesty.

Concluding remarks

If you are feeling overwhelmed, that is completely normal. Applying to graduate school is a lot, especially on top of everything else you are already doing. Make sure to start early so deadlines don’t sneak up on you. And most importantly, don’t be afraid to reach out to your peers, professors, and advisors for help. They may say “no” but they won’t say “yes” unless you ask!

A special thanks to Michigan State University graduate student Camila Monsalve for her help in brainstorming ideas and advice for this guide. Header Image by Welcome to all and thank you for your visit ! ツ from Pixabay

The PER and Science Education grad program lists are a work in progress. If you know of any that aren’t included on those lists, please add them in the comments below!

I am a postdoc in education data science at the University of Michigan and the founder of PERbites. I’m interested in applying data science techniques to analyze educational datasets and improve higher education for all students

Are there PER programs that take teachers as PhD students? I’m thinking about going back, but I’ve been out of college for about twenty-five years…

I think this really depends on the program and their requirements. For example, my group has had PhD students employed at a different university to teach while still working toward their degree. I believe this student had already completed their coursework however.

Yes, definitely. I’ve worked with teachers who are concurrent PhD students; teachers who are on leave from the district to be students; and former teachers who are full-time students. Details vary by institution and by department, so definitely contact prospective advisors to see what your options are.

Thank you to both of you.